Yesterday I had the privilege of joining Dr. Mark Meyer, Hebrew specialist at LBC|Capital, at their D.C. location (Greenbelt, MD) for a workshop, Unpacking Sacred Scripture. We worked together in Psalms 1 and 2, the introduction to the Psalter, to show the combined exegetical and homiletical process. Our goal was to help close the gap between finding meaning and application.

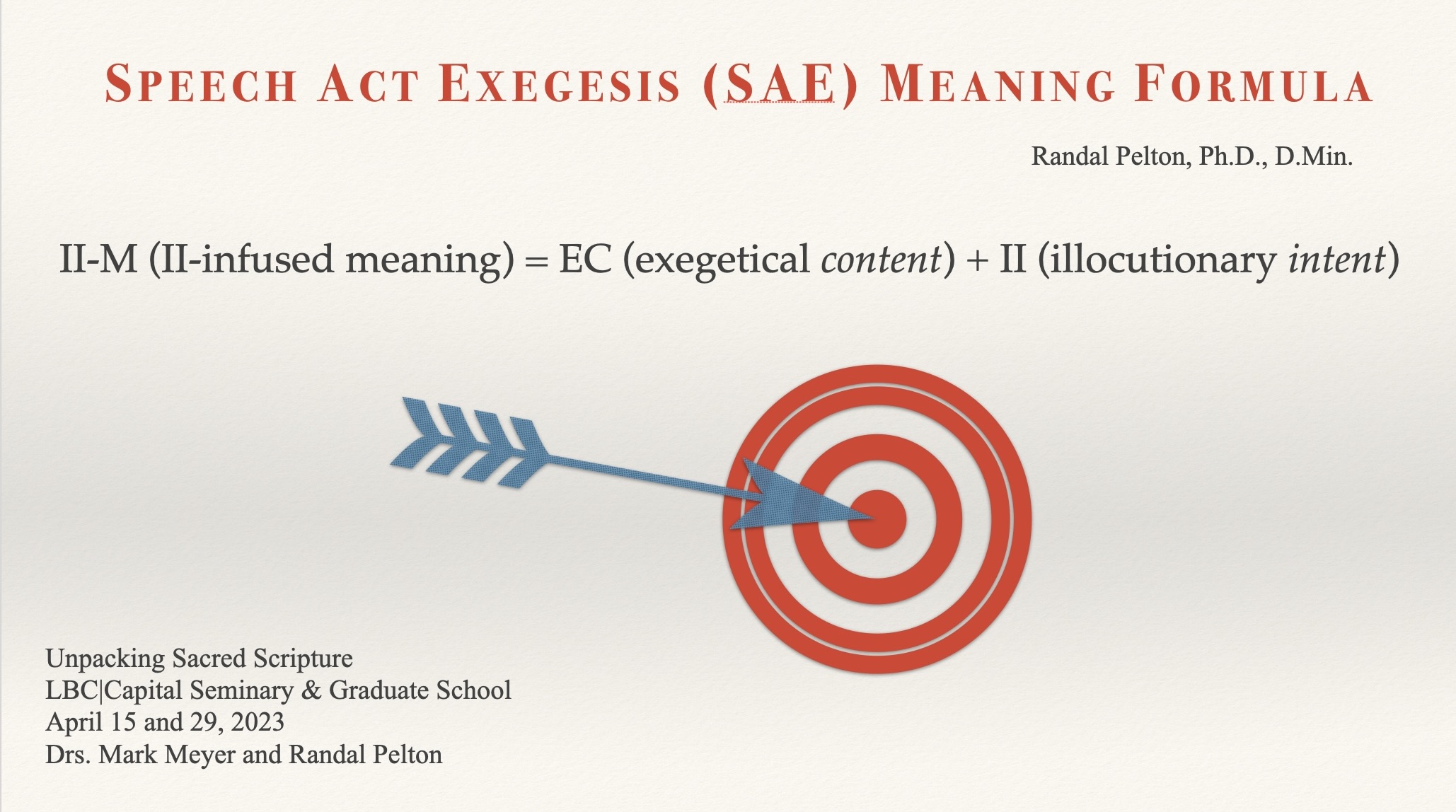

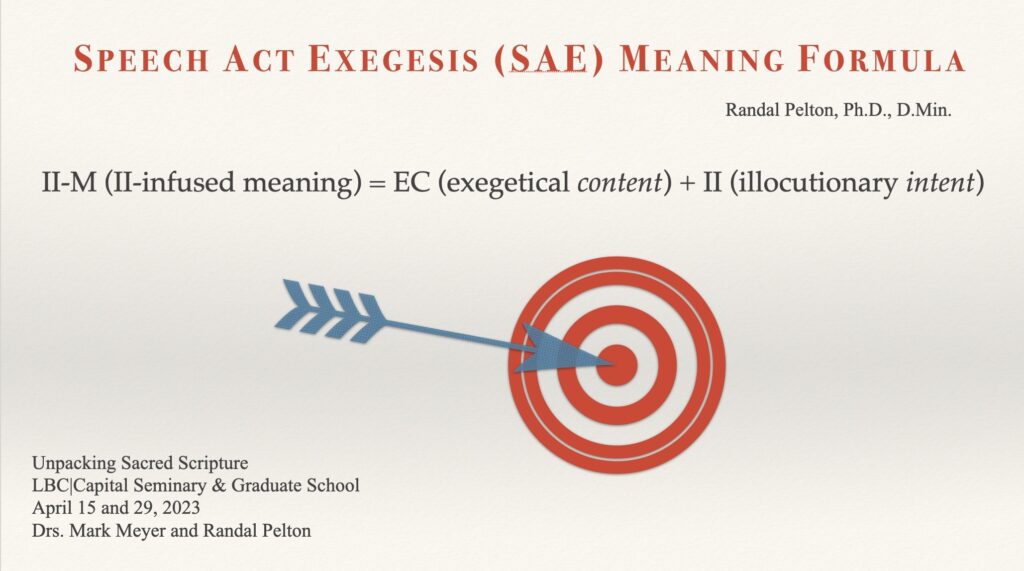

One of my responsibilities was to introduce the participants to a new kind of meaning summary. You can see that in this slide:

Consider this kind of meaning to be your goal as you begin sermon or lesson preparation this week.

I call our target meaning, illocutionary intent-infused meaning (II-M). I’ll spare you the boring details and only say that this fancy language originates from Speech Act Theory and their concept of illocution. Illocution describes what a person is doing by what they are saying.

My favorite illustration of the illocutionary element of communication is my wife, Michele, saying, “Ran, the dog needs to go out.” If I respond with, “That’s nice, Dear,” and go back to my very important job of writing a blog post, then I missed what she meant. In saying, “The dog needs to go out,” she’s really asking me to take the dog out. That’s what she was doing in what she was saying.

As you can see from the slide, II-M is the combination of biblical content and biblical intent. The intent part is critical because this contains the seeds of valid application derived from the meaning of the text.

So, before Sunday, see if you can detect your pericope’s intent. Answer this question from your text:

What does God intend for this Scripture to do to the listener?

If you can add intention to your meaning summaries, you will always keep primary application tied directly to meaning. And, I am suggesting that we really do not know what a Scripture means until we have identified how God intends for it to function for the church.

So, as you begin to identify the meaning of your upcoming Text, complete the meaning summary by adding: “____________ with the intent of_________”

May our Lord receive glory in the church and in Christ Jesus (Ephesians 3:21) as we communicate both content and intent.

Randal