Photo by Allie on Unsplash

Several months ago I decided to go back to getting a newspaper again. I was close to getting a subscription to digital curated news, such as Apple News, but the reviews were not great. I chose the Wall Street Journal thanks to a generous discount for educators. Or, was it students? That’s not important right now.

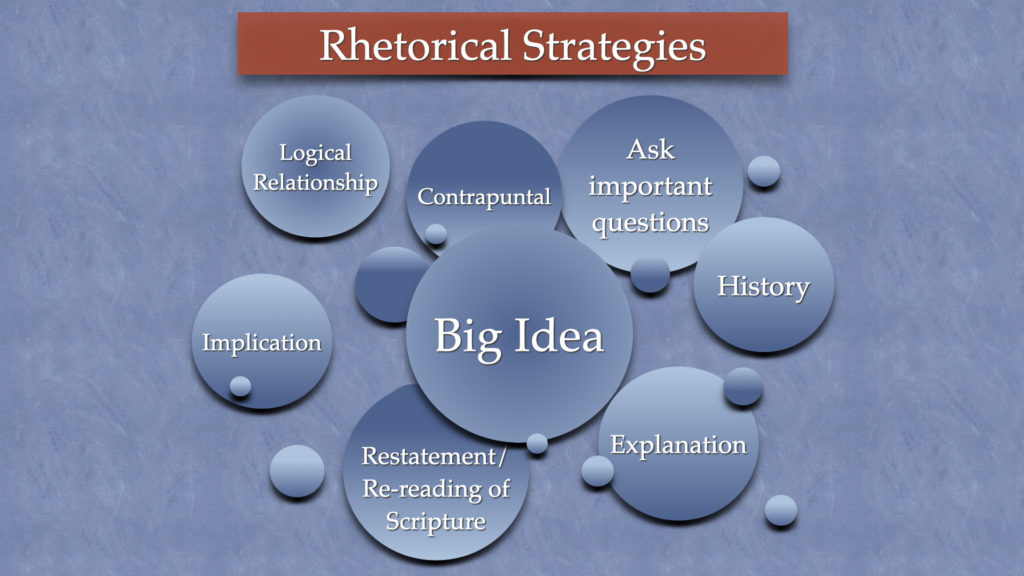

What is important is how the quality of WSJ’s writers is helping me be a better communicator of God’s Word.

Here are some lines from this weekend’s WSJ from one of my favorite writers, Peggy Noonan’s, Declarations: The GOP Tries to Make Its Case…

“If you weren’t moved by [Jon Ponder’s speech] you don’t do moved.”

Or, the reporting of Sen. Tim Scott’s speech which included the phrase,

“Because of the evolution of the Southern heart.” (explaining how “a black man who started with nothing [ended up in “Congress in an overwhelmingly white district in Charleston and beat the field, including the son of former-Sen. Strom Thurmond.”].

Or…

“[Republicans] hit on the one fear shared equally now by the rich, the poor and the middle: that when you call 911 you’ll go to voicemail.”

Or, my new favorite word I read several days ago: humblebrag.

So, in Psalm 18:23 David commits humblebrag when he claims: “I was blameless before him, and I kept myself from my guilt.” Much different than David’s confession in Psalm 38:18 “I confess my iniquity; I am sorry for my sin.”

There are several times in the earlier Psalms when David voices humblebrag. It’s a great word to describe how David can crow even though there were many times he had to eat crow.

I just wished I had remembered to say it in the sermon. Oh well.

May our Lord receive glory in the church and in Christ Jesus (Ephesians 3:21) because of our attempts to become better wordsmiths.

Randal